French investigation board BEA today released a third report about Air France flight AF447. The Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP crashed into the Atlantic Ocean on 31 May 2009. This report current interim report has been made possible by the complete readout of the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) and the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), which were recovered at the beginning of May 2011 after several campaigns of sea searches. According to the report the crisis arose after a problem involving blocked pitot tubes (devices that measure a plane’s air speed), which led to the disconnection of the autopilot. The pilots failed to discuss repeated stall warnings and “had received no high altitude training” to deal with the situation. The pilots got conflicting air speed readings and after the stall, responded by pointing the nose upward, rather than downward, to recover. They failed to regain control of the aircraft and no announcement was made to the passengers before it crashed into the ocean.

The flight can be broken down into three phases:

Phase 1: from the beginning of the CVR recording until the disconnection of the autopilot

Shortly after midnight the airplane was in cruise at flight level 350. Autopilot 2 and autothrust were engaged. The flight was calm. The crew was in contact with Recife ATC centre. The Captain proposed that the copilot take a rest due to the length of his shift. The latter answered that he didn’t feel like sleeping. A 1 h 55, the Captain woke the second copilot and announced “[…] he’s going to take my place”. Between 1 h 59 min 32 and 2 h 01 min 46, the Captain attended the briefing between the two copilots, during which the PF said, in particular “the little bit of turbulence that you just saw […] we should find the same ahead […] we’re in the cloud layer unfortunately we can’t climb much for the moment because the temperature is falling more slowly than forecast” and that “the logon with Dakar failed”. The Captain left the cockpit. The Captain’s departure occurred without clear operational instructions. There was no explicit task-sharing between the two copilots. Some minutes later the crew decided to reduce the speed to about Mach 0.8 because of slightly increased turbulence.

Phase 2: from the disconnection of the autopilot to the triggering of the stall warning

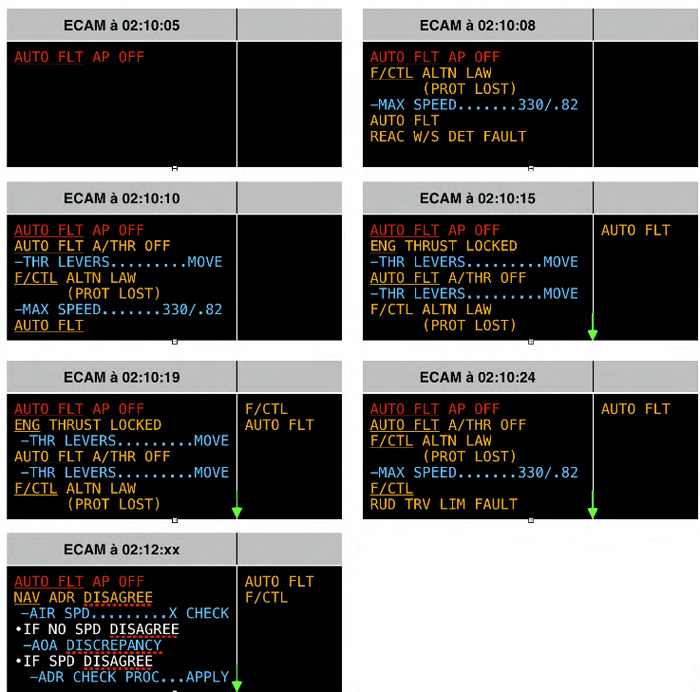

At 2 h 10 min 05, the autopilot then auto-thrust disengaged and the PF said “I have the controls”. The airplane began to roll to the right and the PF made a left nose-up input. The stall warning sounded twice in a row. The recorded parameters show a sharp fall from about 275 kt to 60 kt in the speed displayed on the left primary flight display (PFD), then a few moments later in the speed displayed on the integrated standby instrument system (ISIS). The AP disconnected while the airplane was flying at upper limit of a slightly turbulent cloud layer. There was an inconsistency between the measured speeds, likely as a result of the obstruction of the Pitot probes in an ice crystal environment. At the time of the autopilot disconnection, the Captain was still resting.

At 2 h 10 min 16, the PNF said “so, we’ve lost the speeds” then “alternate law protections […]”. The airplane’s pitch attitude increased progressively beyond 10 degrees and the plane started to climb. Even though they identified and announced the loss of the speed indications, neither of the two copilots called the procedure “Unreliable IAS”. The copilots had received no high altitude training for the “Unreliable IAS” procedure and manual aircraft handling. No standard callouts regarding the differences in pitch attitude and vertical speed were made. There is no CRM training for a crew made up of two copilots in a situation with a relief Captain. The crew composition was in accordance with the operator’s procedures.

The PF made nose-down inputs alternately to the right and to the left. The climb speed, qui which had reached 7,000 ft/min, dropped to 700 ft/min and the roll varied between 12 degrees to the right and 10 degrees to the left. The speed indicated on the left side increased suddenly to 215 kt (Mach 0.68). The speed displayed on the left PFD remained invalid for 29 seconds. The airplane was then at an altitude of about 37,500 ft and the recorded angle of attack was around 4 degrees. From 2 h 10 min 50, the PNF tried several times to call the Captain back.

Phase 3: from the triggering of the stall warning to the end of the flight

At 2 h 10 min 51, the stall warning triggered again. The PF applied TO/GA thrust and maintained his nose-up input. The recorded angle of attack, of the order of 6 degrees at the triggering of the stall warning, continued to increase. The trimmable horizontal stabiliser (THS) began moving and passed from 3 to 13 degrees nose-up in about 1 minute; it remained in this position until the end of the flight. The approach to stall was characterised by the triggering of the warning, then the appearance of buffet. In less than one minute after the disconnection of the autopilot, the airplane was outside its flight envelope following the manual inputs that were mainly nose-up. Until the airplane was outside its flight envelope, the airplane’s longitudinal movements were consistent with the position of the flight control surfaces. Neither of the pilots made any reference to the stall warning and neither of the pilots formally identified the stall situation. About fifteen seconds later, the speed displayed on the ISIS increased suddenly towards 185 kt. The invalidity of the speed displayed on the ISIS lasted 54 seconds. It was then consistent with the other speed displayed. The PF continued to make nose-up inputs. The airplane’s altitude reached its maximum of about 38,000 ft; its pitch attitude and its angle of attack were 16 degrees. At 2 h 11 min 42, about 1 min 30 after the autopilot disconnection, the Captain came back into the cockpit. In the following seconds, all of the recorded speeds became invalid and the stall warning stopped. By design, when the speed measurements were lower than 60 kts, the 3 angle of attack values became invalid. The angle of attack is the parameter that enables the stall warning to be triggered. If the angle of attack values become invalid, the stall warning stops.

The altitude was then around 35,000 ft, the angle of attack exceeded 40 degrees and the vertical speed was around -10 000 ft/min. The airplane’s pitch attitude did not exceed 15 degrees and the engine N1 was close to 100%. The airplane was subject to roll oscillations that sometimes reached 40 degrees. The PF made a nose-up left input on the sidestick to the stop that lasted around 30 seconds.

At 2 h 12 min 02, the PF said “I don’t have any more indications”, and the PNF said “we have no valid indications”. At that moment, the thrust levers were in the IDLE detent and the engines’ N1’s were at 55%. Around fifteen seconds later, the PF made pitch-down inputs. In the following moments, the angle of attack decreased, the speeds became valid again and the stall warning was triggered again.

At 2 h 13 min 32, the PF said “we’re going to arrive at level one hundred”. About fifteen seconds later, simultaneous inputs by both pilots on the sidesticks were recorded and the PF said “go ahead you have the controls”. The angle of attack, when it was valid, always remained above 35 degrees.

Throughout the flight, the movements of the elevator and the THS were consistent with the pilot ’s inputs. The engines were working and always responded to the crew’s inputs. The recordings stopped at 2 h 14 min 28. The last recorded values were a vertical speed of -10,912 ft/min, a ground speed of 107 kt, pitch attitude of 16.2 degrees nose-up, roll angle of 5.3 degrees left and a magnetic heading of 270 degrees.

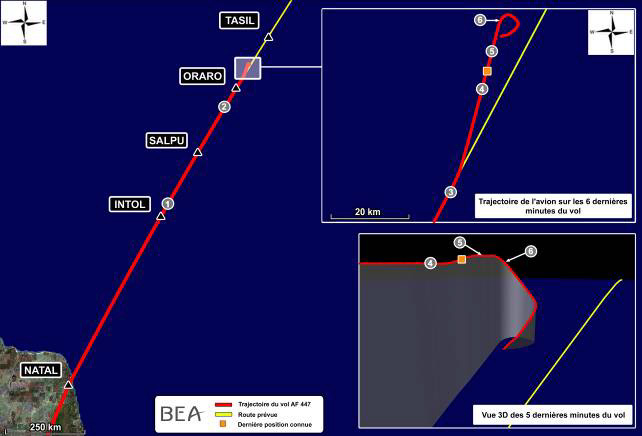

No emergency message was sent by the crew. The wreckage was found 6.5 nautical miles north-north-east of the last position transmitted by the airplane.

Based on analysis of the flight recorders, French investigation board issued several new safety recommendations.

They recommend that the regulatory authorities re-examine the content of training and check programmes and in particular make mandatory the creation of regular specific exercises aimed at manual

airplane handling. Approach to and recovery from stall, including at high altitude.

In addition they recommend that the regulatory authorities define additional criteria for access to the role of relief Captain in order to ensure better task-sharing in case of relief crews.

The regulatory authorities should evaluate the relevance of requiring the presence of an angle of attack indicator directly accessible to pilots on board airplanes.

They also recommend that the regulatory authorities require that aircraft undertaking public transport flights with passengers be equipped with an image recorder that makes it possible to observe the whole of the instrument panel and that regulatory authorities make mandatory the triggering of data transmission to facilitate localisation when an emergency situation is detected on board. They recommend to study the possibility of making mandatory the activation of the Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) when an emergency situation is detected on board.

Source: BEA